Rolex Testimonee and Master of Cinema of Cinema Kathryn Bigelow goes where No Woman has gone

The first and only woman ever with an Oscar for directing, Kathryn Bigelow found that when her mentor Lawrence Weiner challenged and frustrated her, he effectively shaped her creative process

Kathryn Bigelow is the first — and still only — woman to ever win the Academy Award for Best Director. The auteur of 2008’s The Hurt Locker, had originally studied painting at the San Francisco Art Institute, eking out a humble living as a painter while staying with her first two influences, American painter and filmmaker Julian Schnabel and influential performance artist Vito Acconci. Not long after, she entered the graduate film program at Columbia University, where she studied theory and criticism under mentors like Acconci, Susan Sontag, and Lawrence Weiner.

If there’s specific resistance to women making movies, I just choose to ignore that as an obstacle for two reasons: I can’t change my gender, and I refuse to stop making movies.

Rolex Testimonee and Master of Cinema Kathryn Bigelow Goes where No Woman has gone before

Though many remember her first directorial debut The Loveless, as her first feature film to gain critical acclaim in 1981. Bigelow recalled during a 1995 interview that it was her experimental short film and MFA thesis The Set-Up that caught the eye of Academy Award winning director Jan Tomáš “Miloš” Forman. It was this early success that determined the tone and tenor of her cinematic instincts. It is through her graduate film that one can trace her unconventional approach to action cinema and her signature visual aesthetics when she directed 1990s action films such as Blue Steel (1990), Point Break (1991) and Strange Days (1995), written and produced by fellow Rolex Testimonee James Cameron.

Genesis of Inspiration and the perpetuation of Knowledge

A silhouette of Kathryn Bigelow before her mentor Lawrence Weiner

Long before she studied under Lawrence Weiner at Columbia, the pair had began collaborating in the early 1970s, often appearing in or editing his moving-image works and contributing to scripts. It is here that she honed her signature use of audio to dissect images, experimentation with the inherent properties of film and video, to create an engagement with the active viewer, that we see replicated in her seminal works like The Set-Up, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty and most recently, Detroit.

Weiner was a pioneer in the formation of conceptual art in the 1960s. Weiner had met Bigelow at a party at Gordon Matta-Clark’s house in Soho in the early 1970s, when she was 22. “He (Weiner) transferred that (philosophy the work is more important than the finished art object) to people, like me,” said Bigelow, “I found it to be a very exciting, transformative period, and you carry it with you in some way. It becomes part of your creative and intellectual construct and comes out in the work you do forever.”

Indeed, before she even enrolled for graduate studies in film, Weiner was Bigelow’s official mentor for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Program in New York City, and as a result, the two would become close and still remain so today, having made several films together.

You can never unlearn what you learn, you can never unknow what you know. – Bigelow on the transferring of knowledge

Bigelow looks fondly on her time working and learning under Weiner, “It is really a process of transferring information, transferring knowledge, a way of thinking, and it’s unconscious.” An assessment that her mentor agrees with, “Everybody worked with everybody,” He said. “You’re talking about a context that for the past 25 years has not existed, that a person coming in to New York City could find themselves with older artists and somehow or another survive without the grinding and all that.”

There’s no question that knowledge transfer is a dialectic. Weiner challenged Bigelow constantly, shaping her creative decisions through constant dialogue and conversation, posing existential questions that Bigelow found simultaneously exciting and frustrating, to her, these were the genesis of inspiration.

The Light in the Darkness: Creating harmony out of contrast

Though Bigelow is reticent about discussing details of her time in New York during the 1970s, the politics in the air had an effect on Bigelow’s artistic development and it is reflected in the political action thriller Zero Dark Thirty. New York was enduring some hard times and social conditions like these often sparked creativity: artists like Bigelow were essentially exploring their milieu; it is during this time that Bigelow established her creative and intellectual voice when she started working with Art & Language. The artist collective was serious about disruption, merging the practical, leftist politics of the time with the philosophical politics of literary theory of which Weiner was a major contributor creatively.

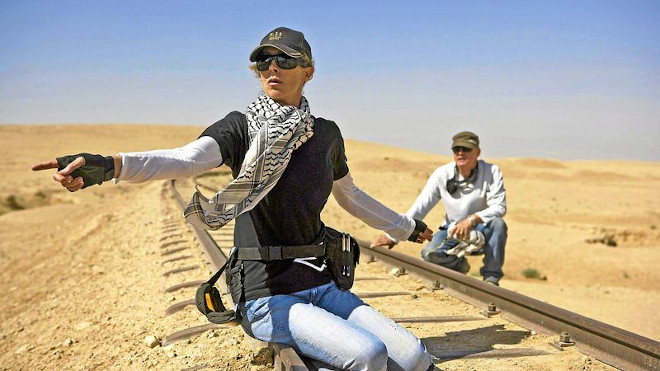

Kathryn Bigelow on set of Zero Dark Thirty

“Lawrence Weiner opened my eyes to the process of both examination and surprise, and how art can enhance, inform,” recollects Bigelow. Without a doubt, when one internalises a particular work, or object, or text or a film, is transformative, it changes the way you see, your perception of the universe. Bigelow describes it with an analogy: “Think of a coral reef with all these schools of fish. Those are all your influences. You’re swimming in this world and then they’re all around you. You are part of that coral reef that has influenced you, that has brushed up against you, been kind to you, been cruel to you. It is the sea of life that washes over you, buffets you like a current and you just try to stay afloat. There are times when you’re gasping for air. It is a challenging, rigorous process, especially if you’re being inspired by somebody who is so extraordinary and intimidating and humbling. It’s just transformative, there is no other way to describe it.”

It’s hard to imagine that close to 50 years on, Bigelow has refined and mastered a cinematographic technique every bit as iconic as her choice: the Oyster Perpetual Datejust 36. An archetypical classic watch thanks to a functional yet sophisticated design that never goes out of fashion, the diamond-set fluted 18 ct Everose gold bezel reflects the elegance of her owner. Like her, the Datejust has spanned eras while retaining the enduring aesthetic that make it so distinctive. Launched in 1945, it was the first self-winding waterproof chronometer wristwatch to display the date in a window at 3 o’clock on the dial, and consolidated all the major innovations that Rolex had contributed, defining the modern wristwatch just as Bigelow has come to define the genre of contemporary political action thrillers.

Discover more about Rolex Master of Cinema Kathryn Bigelow