Jonathan Anderson in Conversation With His Early Inspirations, Gilbert & George

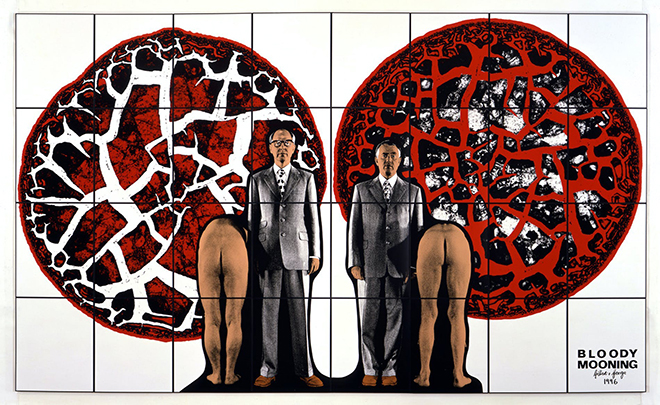

The “machiavellian” Jonathan Anderson enters in conversation with his two biggest artist inspirations, Gilbert & George.

Regarded fashion’s most eagerly watched designer, Jonathan Anderson — who helms JW Anderson and Loewe — is a proud overachiever, with a flair for all things young and rebellious. Stacking newfound accolades year after year, the designer is a permanent jury member for the LVMH Prize and was named a trustee of the Victoria & Albert Museum by former UK Prime Minister Theresa May in 2019. Revered for his quirky sartorial signature, Jonathan Anderson once described his own ambition as “Machiavellian”, owning an innate obsession to the best in all his endeavours.

Gilbert & George with their Object Sculptures on the roof of St Martin’s School of Art, London, 1968.

Entering in conversation with artistic duo, Gilbert & George, Jonathan Anderson has never shied away from expressing his deep admiration for the two. Idolised as two people coming together to become one artist, Gilbert & George have always lived their art as ‘messengers of a new vision’, from the time they met at St. Martin’s School of Art, London, in 1967. Having previously collaborated with Anderson in 2018, this conversation serves as a reminder of how fashion has long proved to progress in a constant nonlinear cycle, with multiple generations drawing inspiration from one another.

- Anderson’s debut Spring/Summer 2015 collection for Loewe.

- Anderson’s debut Spring/Summer 2015 collection for Loewe.

Do you believe there is a relationship between art and fashion?

GILBERT: None. Absolutely none. We never looked at fashion. When we started to walk the streets of London in 1968, we wanted to be ourselves in a big way. That’s why we owned the suits of our responsibility. As lower-class people, we believe it’s very important that you put on a suit for an important occasion. If you go out for a job or go to a wedding or a funeral or a christening, you put on a suit. And we believe that every single day of our life is very important.

GEORGE: If you put a suit from every decade of the last 100 years into a computer and you press the average button, it would come up with something like the suits we wear every day. We also quite like Oscar Wilde, who, of course, said that fashion is horrible, which is why it has to change so often.

Gilbert & George, 2015 © Gilbert & George. Courtesy of the artists and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong, Seoul and London.

JONATHAN ANDERSON: Gilbert and George, I was very influenced by your work when I was at university, and I thought our collaboration [in 2018 with JW Anderson] was a very good platform to speak to younger people about it. There’s a beauty in British humour that I’ve always liked. When you look at the early ’80s series that you did, the men are incredibly seductive. They are people that you want to look up to. Our collaboration was ultimately about my admiration.

Jonathan, you were recently named to the board of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

JA: Yes, and it’s interesting that Gilbert & George mentioned Oscar Wilde. When I think of suiting, Oscar Wilde’s chocolate velvet suit stands out, and the V&A just recently acquired it. George, you’re very right. Other than lapels and the waist, the suit has had only subtle changes throughout the last 100 years.

GEORGE: We always want to stand out and yet blend in at the same time. There’s also an enormous practicality to suits: you are hardly ever searched at airports, and you can get a table at any restaurant in the world.

GILBERT: From the beginning, it was very important to us that we were not making the art. We were the art.

Would you say that wearing your “Sunday best” has allowed you to get away with murder?

GILBERT: Oh we do! We still do get away with murder, yes. We were able to hide in a big and fantastic way.

GEORGE: Dressed like this, we can do whatever we want. The city suit is the modern version of the Norman Knight. It’s male armour, yes?

JA: Yes! I always think the inside of a suit is so fascinating. I am particularly attracted to the chest’s canvas: the sponginess and the horse hair. There’s something about the materials that, when put together, become this strange membrane.

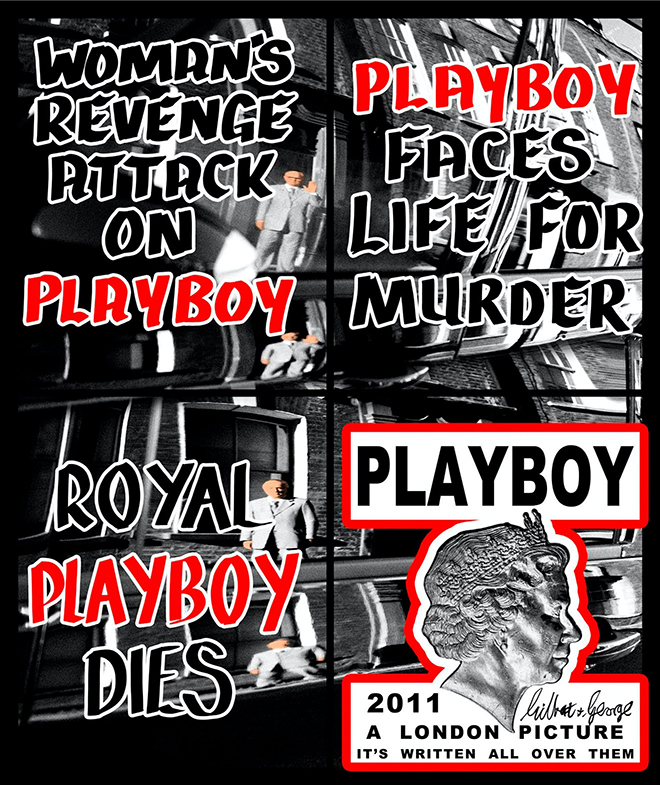

- “Trapped”, 1980, by Gilbert & George; “Union Dance”, 2008, by Gilbert & George.

- “Trapped”, 1980, by Gilbert & George; “Union Dance”, 2008, by Gilbert & George.

For you, Jonathan, what is fashion’s role?

JA: I grew up in Northern Ireland. Fashion was never really embraced as much. Clothing for me really became a form of a weapon. We all become characters in a way when we’re going to work or going for a night out. Fashion can be used for comfort and excess or it can be used as a way of protecting oneself. Ultimately, it can be a very powerful character tool. I like sitting in a park and looking at what people are wearing. I’m interested in their attitudes, in what makes them hold themselves a certain way. Fashion is powerful in that you can really tell the period you’re in.

GILBERT: But for us, fashion is against our religion. It really is, because we made the decision to put our suits on and, like a monk, it’s for life.

GEORGE: We also realised many, many years ago as baby artists that the young people in London who wore suits had to throw them out every two years. They had to buy new suits to stay fashionable, while we always wore the same ones… Not completely the same, but roughly the same all the time.

- Looks from the Loewe Fall/Winter 2020 men’s show.

- Looks from the Loewe Fall/Winter 2020 men’s show.

Whereas Gilbert & George are two people but one artist, Jonathan, you’re one designer with a double persona. You design for both your own brand, JW Anderson, and the Spanish luxury house Loewe.

JA: I don’t know if you’ve seen the movie Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory with Gene Wilder, who, as Willy, has to be told not to do something in order to do it. I don’t believe that clothing is either for a man or a woman. It’s what you feel that you want to put on. All of this came through when I was a kid and I would go shopping with my mother, who would say, “A woman’s closure goes one way and a man’s closure goes the other.” That felt ridiculous to me, and it led me to go out and agitate the norms with JW. At Loewe, I feel like I’m a chic-er form of myself. And the best part is that I have the Eurostar to get myself into character by the time I get to [Loewe’s headquarters in] Paris.

- A sweater, bag, and jacket from the 2018 JW Anderson x Gilbert & George capsule collection.

- A sweater, bag, and jacket from the 2018 JW Anderson x Gilbert & George capsule collection.

- A sweater, bag, and jacket from the 2018 JW Anderson x Gilbert & George capsule collection.

Gilbert & George, you’ve been working on a series of works entitled the New Normal. How has that process been?

GEORGE: We’re very excited. We really feel that we’ve “hit it off”, as they say.

GILBERT: The idea came from walking the streets of Spitalfields. We wanted to find a name that could explain “existentialism” in English. And it’s not “normal”, normal would be that. We always call the new pictures “new”, so New Normal pictures.

The pandemic has caused incredible disruption both in the art and fashion worlds. The art fairs are now viewing rooms and fashion consists of phygital endeavours. How has this changed your processes?

GILBERT: It hasn’t at all, because at the moment we have full exhibitions still going on, so we’ve been working day and night. We’ve not stopped for a single day throughout the entire pandemic, not once.

JA: Well, fashion has really changed. I think it was coming to the end of its cycle anyway, and the coronavirus then obliterated it. The pandemic has marked fashion in the face and said, “It’s time to change.” It’s a scary moment for fashion, but at the same time, I find it quite liberating. I have more time to contemplate on clothing and to read even more. What I’ve found very challenging at the moment, though, especially living in London, is the widening economic gap between people.

GEORGE: Our main message has always been that people have never been more privileged than they are now. We are all spoiled brats!

What can we do about it?

GEORGE: The artist is not here to congratulate them or pat them on the back for being the way they are. The artist is here to show them that there are other possible ways.

GILBERT: We like the idea of confronting the viewer. That, for us, is art.

GEORGE: We are often asked why we want to be provocative. We’re not provocative, certainly not. We would never want to be provocative — we simply want to provoke thought.

“Art for All ” has been your motto for a long time.

GILBERT: We came to that title in 1969. We wanted to make art that everybody would be able to read or get something out of

Do you think there can be a “Fashion for All” or something similar?

JA: I do. Sometimes fashion can be very easily pigeonholed into an elite art form, but whether we like it or not, we are all involved in fashion. We all interact with it on a daily basis. I do think we are indirectly involved in this weird public experiment of dressing up.

GILBERT: Fashion is enormous. It’s much bigger than art, because everybody wants to dress up as a big queen and walk the streets of London, no? That’s it. And art is just a referee in some way. We all want to be different. We don’t want to be the same.

Jonathan, how do you see your creative role?

JA: I see myself as curating ideas, bringing different people into rooms to collaborate on different projects. Loewe has an art foundation that promotes and awards prizes in the fields of poetry, dance, photography and arts and crafts. And I think that’s very important.

One of my biggest heroes is William Morris, and I’ve always thought that he was really about putting craftspeople first. Initially, Loewe began as a German cooperative of craftspeople. To this day, the descendants of the original generation are still working at the factory. Ultimately, they’re master craftsmen. They tell me what to do, because they know how to work with the medium of leather, which is incredibly difficult. It is something that was alive, and now has to be reengineered into another shape. It’s a skill that is learned and passed on from generation to generation.

GILBERT: We have been quite involved with the Arts and Crafts movement. We probably have one of the biggest collections of that period.

GEORGE: Our art is handmade, but nobody will see that and we don’t want them to, anyway. We want them to think that it’s shot straight from the heads onto the wall.

JA: I’ve been very privileged to come to your home and I’ve seen the kind of paradox between Arts and Crafts and your external vision. There’s this madness in the juxtaposition.

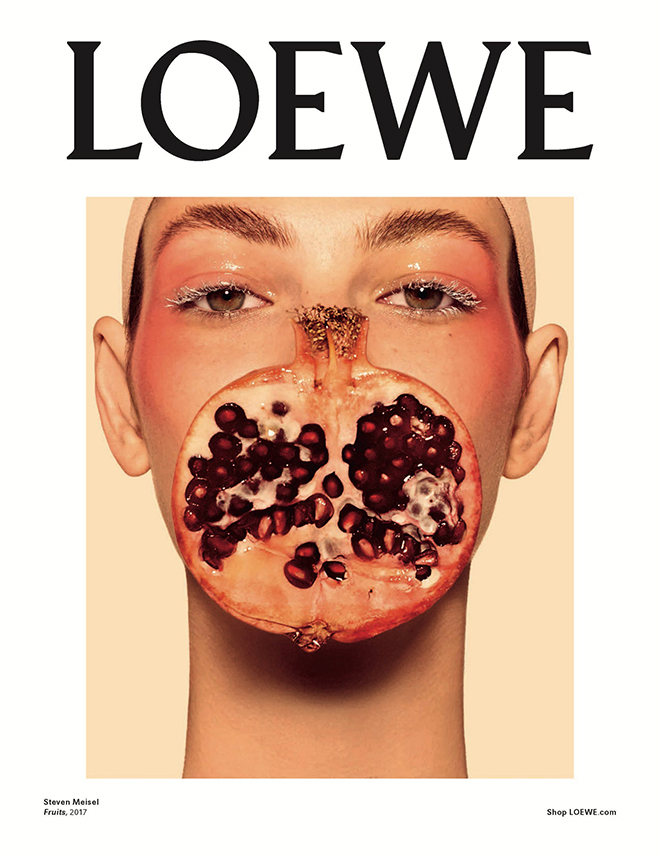

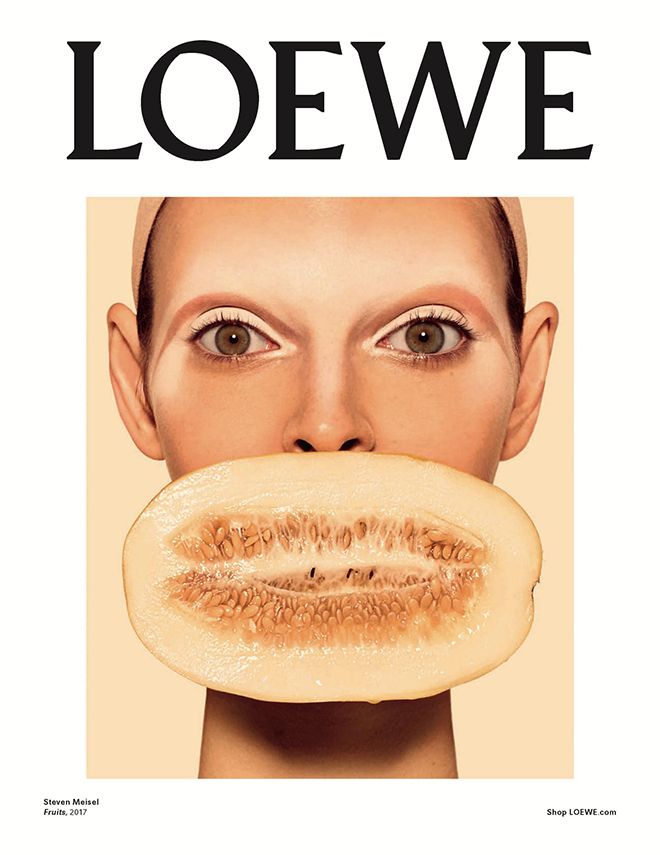

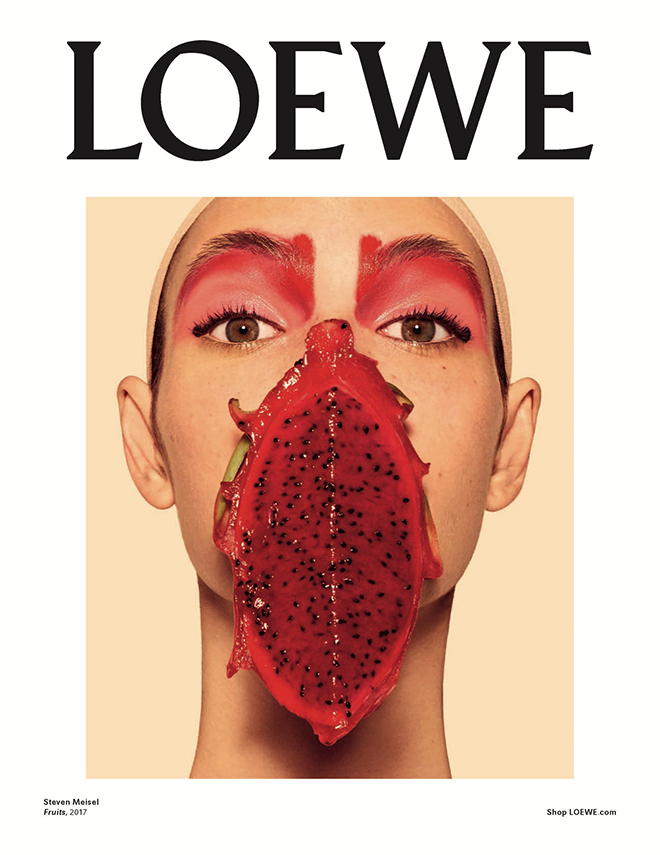

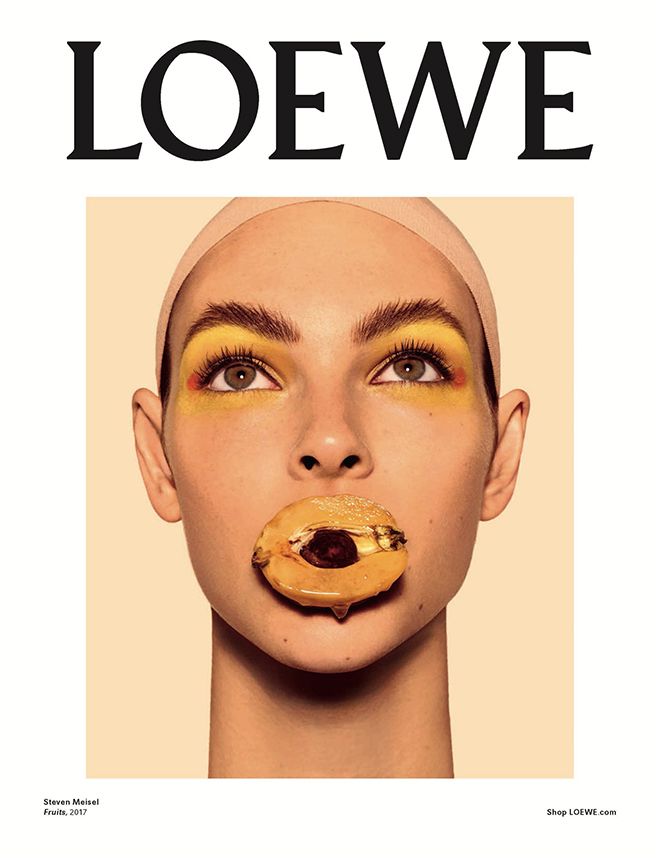

- Loewe’s Spring/Summer 2018 campaign photographed by Steven Meisel.

- Loewe’s Spring/Summer 2018 campaign photographed by Steven Meisel.

- Loewe’s Spring/Summer 2018 campaign photographed by Steven Meisel.

- Loewe’s Spring/Summer 2018 campaign photographed by Steven Meisel.

How does seduction play into your work?

GEORGE: Very important. We want to seduce the viewer. We want the viewer to at least say, “What the hell am I supposed to think?” We want them to go away and be different. We like it when the elderly gentleman with two walking sticks comes over and says, “This is a tremendous exhibition as it sure scares the hell out of me.” We want to affect others.

GILBERT: And we do.

What is the importance of luck in your life and in your work?

GILBERT: Ah! Fate! It’s all about accidents with fate. Everything we do is by accident and nothing else. What do you think, George?

GEORGE: When we go to the studio to create new pictures, we go empty-headed. We lift the pictures out from inside of ourselves without being conscious of what we’re doing. If we were conscious in our planning, we would never do the pictures that we do.

Jonathan, in 2016 you curated an exhibition, Disobedient Bodies. What was that like?

JA: I was asked by the Barbara Hepworth museum in Wakefield to collaborate on an exhibition project. At the same time, a museum institution in London invited me to do a retrospective. I thought it was a very strange thing to do at my age at the time. It was also during an odd political moment in Britain. I was fed up with everything in London and with big institutions, so I decided that it was better to do it in Wakefield, because I felt it was about not making it so London-centric. I came up with the idea of looking at how artists, fashion designers, architects, potters and dancers interpreted the body, including works from Eileen Gray to Jean Arp. It was a strange process. It took three years to do the show and complete it, but it was an amazing experience

What did you explore with this show?

JA: I was looking at how classical sculpture has been based around our interpretations of the body. I like the idea of ornamentation; that the body becomes this sort of vessel. You’re decorating a precious object, which is the human form. For me, the show was about breaking the rules. I learned the importance of breaking them in any art form to find oneself.

- Images from “Disobedient Bodies”, the exhibition curated by Jonathan Anderson at The Hepworth Wakefield.

- Images from “Disobedient Bodies”, the exhibition curated by Jonathan Anderson at The Hepworth Wakefield.

How do you define beauty and what is its role in your work?

GEORGE: We always say that beauty is there to carry the message. And the colours and shapes are never there to please. They’re there to serve the purpose of bringing the message from us to the viewer.

GILBERT: What is good and what is bad is changing every single day, every time. And we want to be a part of that, deciding it.

GEORGE: Laws are changing all over the world, all the time. Culture is the greatest force. We always say “ban religion” and “decriminalise sex”. Those are our two main mottos.

GILBERT: We want to free ourselves from religion.

GEORGE: I’m always amazed when people ask what we mean by that. They don’t know that as we speak now, there are people lying on the floor of police cells in more than 100 countries all over the world, famished, not knowing whether they will be executed or not, just for having sex. It’s the same with banned religion. We know it’s true because one day we had a knock on our door. It was an elderly clergyman that said, “We love that thing you’re doing, ‘Ban religion’, it’s marvelous.” I said, “Thank you very much, perhaps you can tell me why you think that?” “Oh, it’s very simple,” he said. “I’m getting on with my congregation on Sunday. They’re all friends of mine and are rather religious, but I don’t want them to be religious. I want them to be good.” Great moment.

JA: You guys are so generous and so giving. I think that’s why I love you. When I look at your work, I’m just teleported. There is not much art out there that is so generous. I can sit in front of one of your works with full pleasure and leave with pleasure. It’s incredibly humbling and remarkable.

- Details from the JW Anderson Fall/Winter 2020 men’s show.

- Details from the JW Anderson Fall/Winter 2020 men’s show.

How did you find your signatures?

GEORGE: Well, that’s a very interesting and simple story. Unlike the other students, when we left university, we didn’t have a family safety net. We didn’t have any money, but we knew that we were artists. We wandered the streets of London to find life. We were walking near Euston station, and found a shop selling second-hand things, all the unwanted bits: lampshades, last year’s telephones and all the detritus of human life. Inside, we found a record, which was called Underneath the Arches. We thought it was very strange; very near where we lived at the time, there were tramps underneath the arches like that. We took it to a friend who had a gramophone, and we were astonished. The lyrics identified with how we saw life every day in the East End of London. “The risk we never signed for, the culture they can keep, there’s only one place that I know and…”

GILBERT & GEORGE: [Together singing] “… That is where we sleep. Underneath the arches, I dream my dreams away. Underneath the arches, on cobblestones we lay, every night you’ll find me, tired out and worn…”

GEORGE: And that was the moment we found life.

GILBERT: After that we never changed.

GEORGE: Art was life and life was art. All together.

JA: I don’t think I’d ever be able to beat that act! I feel like I still haven’t found my signature style yet. There’s always a kind of search for something.

–

This article was written by Pamela Golbin and published on L’Officiel Singapore.